The Los Angeles Opera mounted Peggy Woolcock’s production of Bizet’s “The Pearl Fishers” with a cast of international caliber, conducted by Maestro Plácido Domingo.

[Below: A pearl fisher dives for pearls in the Los Angeles Opera’s 2017 performances of Bizet’s “The Pearl Fishers”; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

Nino Machaidze’s Leila

Nino Machaidze, soprano from the Republic of Georgia performed the role of the priestess Leila. Machaidze sang Leila’s principal aria Comme autrefois with a shimmering coloratura, and displayed an elegant legato for her dreamy O Dieu Brahma.

[Below: Nino Machaidze as Leila; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

The Los Angeles Opera identified Machaidze’s star quality at the beginning of her career, when she opened the 2009 season as Adina in Donizetti’s “L’Elisir d’Amore”, subsequently returning for five additional roles highlighted by her Juliette to Vittorio Grigolo’s Roméo in Gounod’s “Roméo et Juliette” (2011) and by her Thaïs to Plácido Domingo’s Athanaël in Massenet’s “Thaïs” (2014).

Javier Camarena’s Nadir

Mexican tenor Javier Camarena, in his Los Angeles Opera debut season, sang the role of Nadir, one of the supreme challenges of the lyric tenor repertory, ascending into the highest range of the tenor voice.

[Below: Javier Camarena as Nadir; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

Camarena delivered Nadir’s aria Je crois encore entendre, with beauty of tone and seeming effortlessness, for which he was greeted by a sustained ovation from the Los Angeles audience.

Alfredo Daza’s Zurga

Mexican baritone Alfredo Daza, the Zurga, shares with Camarena’s Nadir the responsibility for delivering the opera’s showstopping duet Au fond du temple saint, which he and Camarena performed brilliantly for the appreciative Los Angeles Opera audience.

The role of the conflicted Zurga is dramatically the most demanding of the three principals – playing a character whose actions are often indefensible and whose one deed inviting audience sympathy (helping Nadir and Leila escape) is compromised by an unforgivable act of arson.

[Below: Alfredo Daza as Zurga; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

Daza’s vocal expressiveness in performing Bizet’s luxuriously beautiful music, assured audience sympathy for the artist, rather than for his character.

Nicholas Brownlee’s Nourabad and the Los Angeles Opera Chorus

The fourth member of the small cast was Alabama bass-baritone Nicholas Brownlee – a sturdy presence, singing authoritatively as the high priest Nourabad, grappling with the consequences of errancy of the priestess in his charge.

[Below: Nicholas Brownlee as Nourabad; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

As the officiator of the religious ceremonies, Brownlee’s Nourabad inspires the mesmerizing communal prayers sung by the excellent Los Angeles Opera Chorus, under the leadership of chorus director Grant Gershon.

Maestro Plácido Domingo and the Orchestral Performance

Throughout his careers as an operatic tenor and baritone, Plácido Domingo has demonstrated a fondness for and artistic rapport with the French opera repertory. In his parallel career as a conductor, he has often chosen to conduct the French works.

[Below: Maestro Plácido Domingo (bottom right) conducts the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra in a performance of “The Pearl Fishers”; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

Domingo conducted “Pearl Fishers” with the authority of long experience with its music, always respecting Bizet’s melodic score. The Los Angeles Opera Orchestra responded with the solid performance one always expects of it.

Peggy Woolcock’s Production and 59 Productions Video Projections

Bizet’s 1863 opera “Les pêcheurs de perles” has undergone two major transformations in its history – a 1890s revival that revised and recomposed the opera’s concluding segment, adding an inauthentic trio and discarding all copies of Bizet’s orchestration for the original ending.

Eight decades later, conductor Arthur Hammond created a new version, restoring Bizet’s ending and recomposing the lost orchestration. The Los Angeles performances used re-orchestrations from Martin Fitzpatrick, music director of the English National Opera. [For my extended commentary on the original, revised and restored version (in the context of a different production), see A new look for Bizet’s “Pearl Fishers”: Zandra Rhodes in San Diego & San Francisco.]

English director Peggy Woolcock’s production was originally created for English National Opera, with scenery designed by Woolcock’s English colleague, Dick Bird. The setting evokes a seaside village of Sri Lankan shanties occupied by a population living a marginal existence.

Many of Peggy Woolcock’s ideas that inspired this production are praiseworthy. During the prelude, three acrobats on fly-wires dive for pearls behind the scrim.

[Below: three divers search the depths for pearl-bearing oysters; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

The projection designs are created by Britain’s 59 Projections (whose operatic projects included a recent new opera [see World Premiere Review: Ovations for the (R)evolution of Steve Jobs – Santa Fe Opera, July 22, 2017.]

When Zurga and Nadir are sharing remembrances of Leila, whom both love, two fishermen on adjoining balconies throw out a net onto which Leila’s image is projected. Particularly effective were Dick Bird’s sets for the priestess Leila’s refuge on a pier above crashing waves designed by 59 Projections – Leila’s hideaway believable as a barrier to all except the highly-motivated Nadir.

Other ideas evolved from Woolcock’s conviction that any opera about Ceylon (Sri Lanka) should address contemporary concerns – the exploitation of native workers (be it by colonial powers, international corporations or native bureaucracies) and the impact of climate change on communities dependent on the sea.

[Below: Zurga (Alfredo Daza, in blue tunic, center, left) surrounded by the population of the fishing village he leads, welcomes an unknown veiled priestess (Nino Machaidze, center); edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

Often an operatic work is sturdy enough to be transported to times and places that the composer and librettist never imagined, with contemporary concerns imposed on works created in different times for different purposes.

One can be concerned about the impact of rising seas on a coastal town, yet doubt that Bizet’s youthful work can become a useful vehicle for expressing that concern.

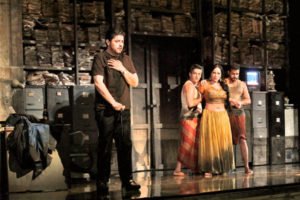

The “exploitation” theme proved especially difficult to pull off in performance. Woolcock, determined to identify Zurga as the operative of an exploiting bureaucracy moved the action closer to our time. A set was designed for Zurga’s paper-filled office with file cabinets and television sets.

Zurga’s office rather implausibly becomes the venue in which Zurga pronounces death sentences on Nadir and Leila. It also provides the setting for Zurga discovering that Leila possesses the necklace he gave a little girl who had saved his life years before.

[Below: Zurga (Alfredo Daza, left) has two villagers bring the blasphemous priestess Leila (Nino Machaidze, second from right) to his company’s office to sentence her to death; edited image, based on a Ken Howard photograph, courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera.]

For a scene that many productions handle simply by moving without a pause from one part of the stage to another, Woolcock has created an entire office set that requires a lowered curtain and a long pause to set it up and another long pause to replace it with a scene of the burning village.

A denouement that was weak enough to bother the original librettists (whose hit operas include Gounod’s “Faust” and “Roméo et Juliette” and Offenbach’s “Tales of Hoffmann”) and to inspire rewriting the ending for the 1890s Parisian revival, is not improved by trying to mix in the idea that Zurga is the operative of a heartless bureaucracy.

Recommendation

I enthusiastically recommend the Los Angeles Opera production of “The Pearl Fishers” for its singing, and often brilliant staging, both for the veteran opera-goer and the person new to opera.